Humans are visual creatures, therefore, the design of our physical surroundings — including landscapes and buildings — can have a significant impact on our psychological state and wellbeing.

The mental and emotional benefits of naturalness, in particular, are widely documented in numerous environmental psychology literature.

Some specific patterns found in nature are called fractals — which are patterns that repeat at different scales. This means if you look closely, you will see the same pattern replicated, and much smaller, inside the larger outline. For example, trees are natural fractals, with visible patterns that repeat smaller and smaller copies of themselves to create the biodiversity of a forest.

Spots, stripes, ripples, branching, spirals, cracks, waves, hexagons and florals are visible regularities of form found in plants and natural systems, including the weather.

For many years, patterns were studied by mathematicians in an attempt to try to understand the order in nature.

Spirals, for example, are so abundant in nature and are commonly seen in plants and in some animals, notably molluscs. You can clearly see the spiral as a flat curve in ferns, but also as a 3D spiral in petals as they unfurl around the flower bud. And because of the sacred quality that humans attribute to nature’s fractal scenery, spirals have been used in a range of religious and sacred architecture.

Psychological benefits of natural patterns

Psychological and physiological benefits of viewing nature environments have been extensively studied for some time. Research shows that being around nature has positive outcome such as stress reduction, improved mood, enhanced attention, and cognitive functioning among other salubrious effects.

Likewise, more recently, it has been suggested that some of these positive effects can be explained by nature’s fractal properties. Natural elements and even representations of them can be found in certain built environments that exhibit visual patterns inspired by biological systems.

Experiments have been done using eye-tracking equipment to better understand how people look at these patterns. Using functional MRI (fMRI) techniques to quantify resulting brain activity, it appears that people are “hard-wired” to respond to certain forms of fractals in nature.

As it turns out, many studies indicate that exposure to fractal patterns in nature reduce people’s levels of stress by as much as 60%. The stress reduction effect transpire due to physiological resonance that takes place within the human eye.

Researchers have also proposed that organic patterns in art, architecture and landscapes may be inherently preferred over synthetic forms, and that exposure to naturalistic architectural spaces may induce many of the psychological benefits of interacting with nature itself. In such built environments, we tend to feel less stressed and anxious, more relaxed and engaged.

This suggests that naturalistic visual patterns reveal rich sensory information similar to what we encounter in our natural surroundings.

Biomorphic forms and patterns

Many buildings across the globe exhibit nature-like characteristics, making them interesting, captivating, contemplative and absorptive. Biomorphic forms and patterns are nature-inspired approaches to design and can apply to architecture, interior and product design. Nature’s living, curving, undulating shapes and patterns have long served as a fruitful source of inspiration for architects and interior designers around the world.

In design, incorporating organic and biomorphic patterns doesn’t necessarily mean using actual living things, but instead seeking to emulate and reference nature. Ultimately, forms and patterns avoid the harsh edges of right angles and straight lines and instead turn towards a high density of curved edges, high frequency of contrast changes and symmetrical moments of interest and captivation.

Whether used in a functional way, as a decorative piece, or a structural aspect of design, biomorphic forms and patterns have been shown to contribute positively to human well-being by reducing physiological stress responses and increasing view preferences — both key to establishing a healthy life balance and enhancing mental health on a large scale.

The aesthetic use of natural patterns

The objective of biomorphic forms & patterns is to provide representational design elements within the built environment that allow users to make connections to nature. The intent is to use natural patterns in a way that creates a more visually preferred environment that enhances cognitive performance, while helping reduce stress.

Humans have been decorating interior spaces with representations of nature since time immemorial, and architects have long created spaces using elements inspired by trees, rocks, bones, wings and seashells.

Many classic building ornaments are derived from natural forms, and countless fabric patterns are based on leaves, flowers, and animal skins. These architectural and design elements evoke sentiments that tap into our inherent responses to the patterns, movement, light, shape and space encountered in nature.

Design considerations that may help create a quality biomorphic condition:

- Apply on 2, or 3 planes or dimensions (e.g., floor or wall plane and wall; furniture windows and soffits) for greater diversity and frequency of exposure.

- Avoid the overuse of forms and patterns that may lead to visual toxicity.

- More comprehensive interventions will be slightly cost-effective when they are introduced early in the design process.

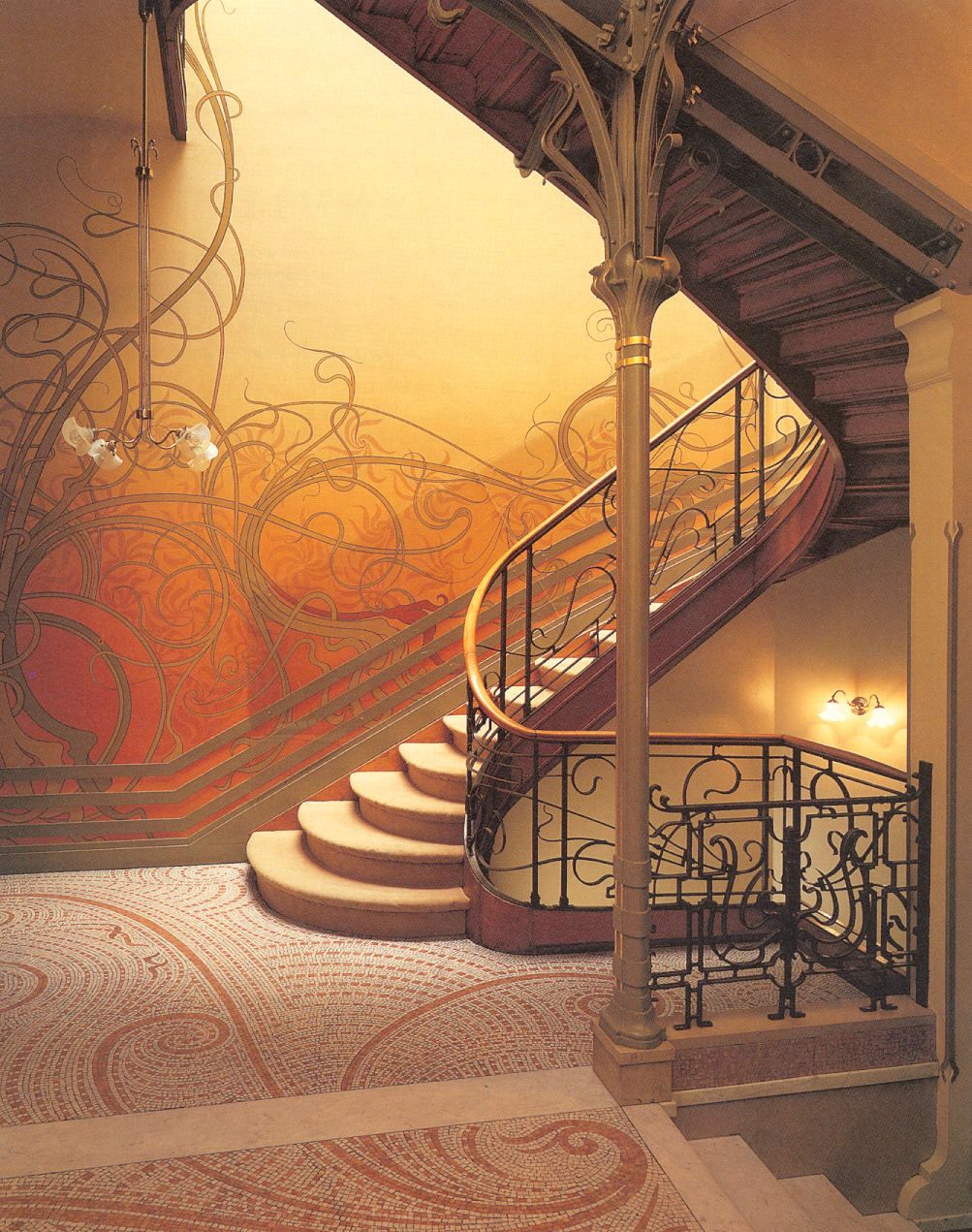

Designed in 1983 by architect Victor Horta, The Art Nouveau Hotel Tassel in Brussels is a prime example of biomorphic patterns.

The beauty of Hotel Tassel is signalled by the use of iron and steel while drawing decorative motifs from nature. The interior space in particular is rife with Horta’s “biomorphic whiplash” design signature: natural analogues, graphic vine-like tendrils painted on the wall and designed into the banisters and railings, floor mosaics, window details, furniture, and columns are the most eye-catching features.

The curvaceous tiered steps seem to make distant reference to shells or botanical forms.

Material connection with nature

Similar to biomorphic patterns, material connection with nature takes its inspiration from the outside world and seeks to incorporate it into the interior environment.

Yet, this pattern specifically features actual materials that make a space feel warm and authentic and sometimes stimulating to the touch.

Material connection with nature pattern is guided by the core belief that human receptors always prefer real to synthetic materials and can tell the difference between the two. Touch is at the centre of this pattern, and creating a space where exploration is encouraged is a major component.

This pattern manifests itself in design through a number of different ways, including the incorporation of a natural colour palette, particularly green to facilitate creativity and cognitive performance — using variety of materials in a single space: wood, stone or dried grasses for example — and the use of these materials in specific ways based on a room’s functional needs: for example, a certain percentage of solid wood flooring in a room can exhibit a significant decrease in blood pressure or serve to encourage restoration or relaxation.

By using natural materials optimal for engendering positive cognitive or physiological responses, we can enhance our ability to grow and thrive within our interior environments.

Conclusion

The primary goal of designing with patterns inspired by nature is to create an enriching environment based on an understanding of the symmetries, fractal geometries and spatial hierarchies found in our natural surroundings. The more in contact we are with nature, the more at-ease we feel.

Humans instinctively respond well to visually interesting spaces. By understanding the mathematics behind complex design and using nature as a guide, we can bring back, conserve, and promote biophilia in modern and future urban systems