You may know his work from the extension to the British National Gallery of Art’s neoclassical building on London’s Trafalgar Square (1986). Then again, perhaps you’re more familiar with the Seattle Art Museum (1991).

[plugmatter_promo box = ‘1’]

Regardless of whichever form of his architecture you are more knowledgeable about, there is no denying that Robert Venturi (now retired) produced work which was daring, unique and incredibly talented – making him one of the most influential individuals in modern architecture today.

Equally as well-known for his writing as his designs, Philadelphia-born Venturi has picked up many accolades during his lengthy and acclaimed career, including the Pritzker Architecture Prize (1991) and the Vincent Scully Prize (2002).

Each new Robert Venturi design was innovative in its own right

‘Futuristic’, ‘unconventional’, ‘eclectic,’ ‘idiosyncratic’ – these are all words which have been used to describe his architectural style over the years. Conversely though Venturi, the son of a grocer, has strived to have no signature style in that every design he has created was accepted for being innovative in its own right.

[plugmatter_promo box = ‘9’]

His designs – which deliberately juxtaposed architectural elements and systems – all have one thing in common though: each is spatially intricate.

Vanna Venturi House – the first postmodernist structure?

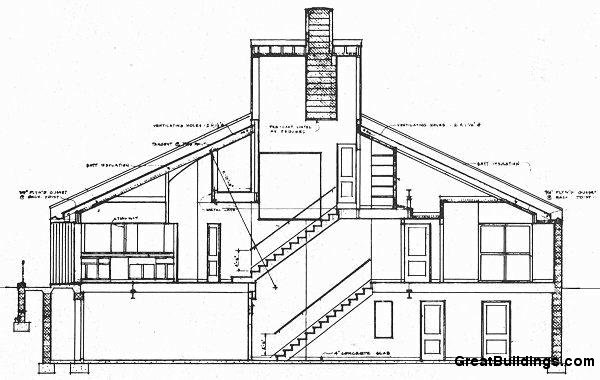

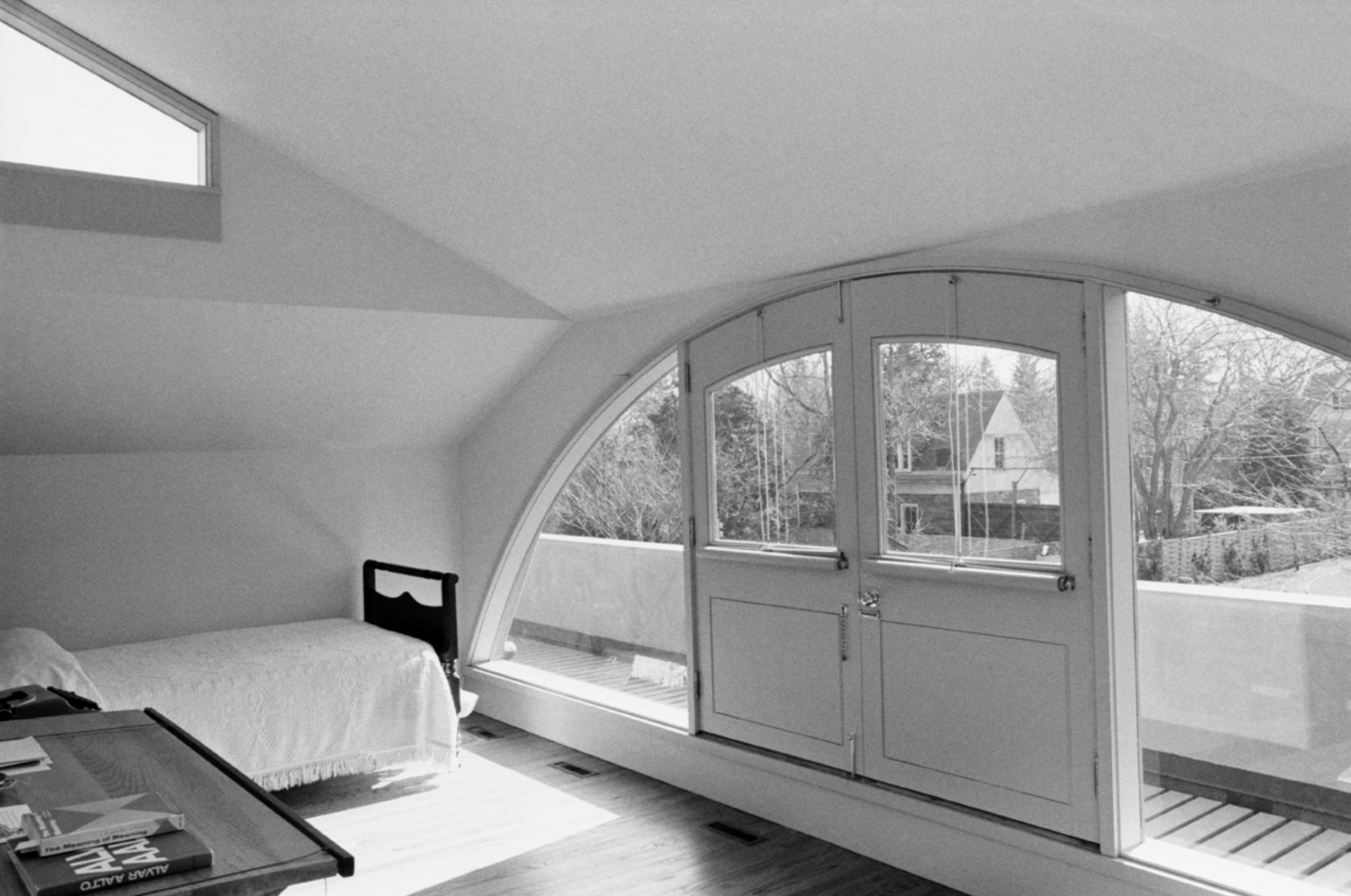

His Vanna Venturi House, created in 1959 and which took six years to complete, challenged the rigid formalist norms of modern architecture. Aged just 34 and working as a teacher at the time, he nevertheless took the decision to shun the great Corbussie’s ‘Less is More’ philosophy for his own: ‘Less is bore,’

Built for his mother the design reinterpreted and made a statement of the archetypal American suburban house, to the extent it is credited as being the first Postmodern building.

You will find that a study of the house shows Modernist architecture used by Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright (horizontal ribbon windows and a simplistic rendered façade) but also includes ornamentation. For instance, the Arch has no function, the stairway is smaller than those of the time and the pitched roof with its over-sized chimney was viewed as elaborate for the time.

Of the building Venturi is quoted as saying: “Some have said my mother’s house looks like a child’s drawing of a house – representing the fundamental aspects of shelter – gable roof, chimney, door and windows. I like to think this is so.”

Another renowned Venturi design was the Episcopal Academy Chapel, also in his native Philadelphia and built in 1960. It combines aesthetics and simple functionality but with an obvious medieval charm:

The spectacular Seattle Art Museum, which sits downtown in the centre of this seap port city, boasts a shimmering steel façade and a very dramatic interior (and where you will also find some world class art works). Again it is creative, but at the same time, very structurally sound:

Across the Atlantic to London where Venturi’s name was already well-known in architectural circles worldwide. Here in the UK he was commissioned to design the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery in the early 1990s – a controversial and changing time in architecture. Again, this extension, which houses a collection of Renaissance paintings, is very ornamental and stylish:

Freedom Plaza in Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington DC which is mainly built of stone and sits above street level, commemorates Dr Martin Luther King, Jr. It was the result of a design competition hosted by the local development corporation, and won by Venturi:

Here at the Reclaimed Flooring Company we provide wood for various projects and invite you to take a look through our website today.